Remember back when I used to do children's chapter book features called The JUV FIC Corner? Yeah, I barely do either - my last one was technically in June of 2013! I say "technically" because I think my overall reading habits have become a lot more juvenile in the past two years thanks to my job, so it's not such a rarity that I focus on children's lit anymore.

More to the point, I started doing those posts several years ago to feature some of my childhood favorites after re-reading them as an adult. It's always a lovely connection to check in with the beloved stories that were such monumental pieces of my reading history. It's difficult, as an adult, to recollect the kind of innocent wonder, intrigue, and impact that is an inherent part of childhood. Re-reading these favorite stories, I think, gives us back a piece of that feeling for just a moment.

I remember discovering Tom's Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce while lying in my grandparents' floor watching Reading Rainbow. After hearing a teaser, I just had to read it. And I must have, at the time, but that time is so long ago, probably 20 years ago at this point, that I can't actually remember much beyond that random day in front of their floor console television set. Something suddenly inspired me to find this book again, and luckily the Nashville Public Library had an original copy available in their annex.

In this lesser-known story (at least to modern American audiences), Tom is sent to spend the summer with his aunt and uncle after his brother contracts the measles. Now living in an upstairs apartment with no garden in which to run around and play, Tom immediately bemoans his lost summer of adventure with his brother Peter. One sleepless night, though, he hears the old grandfather clock downstairs strike a thirteenth hour, and when he goes to investigate, Tom discovers the backdoor now opens into a huge, beautiful garden that definitely wasn't there before... Now, every night when the clock strikes thirteen, Tom escapes to this magical Victoria-era world where he befriends a girl named Hatty who becomes his steadfast companion and playmate.

It's so different from modern stories, yet so alike many classic stories in children's literature where fantasies are actualized. A boy steps outside when the clock strikes a mysterious hour and the whole world is different. The explanation doesn't matter, not yet at least; it's the discovery and exploration that cause the mind-racing, can't sleep kind of anticipation and excitement. This must be where I first fell in love with a time travel story, because the concept is so much a part of the best imaginings - a safe kind of adventure of discovery.

And like many childhood classics, the language is complex, never simplified for an adolescent audience. Pearce jumps a scene to different time, character, or perspective without any warning, in a way that feels apt to scene cuts on film, not narrative in a novel. It's surprising, and delightful, especially to an adult reader like myself, but I wonder about its 21st-century accessibility to young readers. (Most of my technology-dependent modern preteens, sadly, would probably not appreciate the simple imagination of this story.)

To me, though, it's wonderful storytelling and perfectly magical.

Saturday, December 24, 2016

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Nonfiction | Striving for Success in China's Factories

With only two (!!) categories remaining on my seemingly never-ending quest to finish the Read Harder Challenge I began in 2015, I was finally able to pull a title off my existing to-read list for the "book that takes place in Asia." Leslie T. Chang's Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China is a nonfiction exposé on the life of China's numerous (130 million, to be exact) migrant workers. The story is neither thrilling nor uncommon; instead, Chang chronicles the everyday existence of these millions of people that live a life entirely unrelatable to our Western ideals.

Set primarily in the industrial town of Dongguan, Factory Girls tells a common story - that of millions of girls who leave their rural towns for a life and job in the city. As the older generation stays planted in these small, rural towns, continuing a familial tradition of agriculture, the younger generation's future has changed due to China's modern industrialization. Children, particularly the girls, leave for the factories, becoming their families' primary breadwinners. With their migration comes a new sense of freedom and opportunity in a society where education is valued but legitimacy is not (necessarily), where success depends on street smarts, and where, it seems, anything is possible if you work hard enough and smart enough for it.

Chang is a former Wall Street Journal correspondent of Chinese descent. Unfamiliar with, and a bit wary of, her own ancestry, she explores this facet of modern Chinese society from a voyeuristic perspective through select women she follows over the course of three years. She chronicles their move from job to job, always on the lookout for something better, with little loyalty or regard to particular employers; she observes friendships and relationships that seem superficial at best, entirely artificial at worst. It's a world where better jobs often come after lying on your resume, where pyramid schemes and scams run rampant to prey on hopeful ambition, and where relationships can disappear entirely with the simple loss of a cell phone.

The strength of this book lies in Chang's straightforward way of reporting the story. It's not a dastardly tale of sweatshop work. The impression I get, in fact, is that the sweatshop horrors is the stereotype of yesteryear. Though the work is certainly more monotonous and demanding of time (6-day work weeks, for example) than we are used to, the conditions, based on Chang's telling, don't seem harsh or cruel. In this sense, it's not a story of drama and hardship; it's the story of how these migrant women are constantly working for betterment. There is no passive acceptance of life; these women strive to educate themselves for better jobs and new opportunities.

Interspersed with the present-lives of Chang's migrant subjects is Chang's own family history as migrants to the U.S. after China's Cultural Revolution. Despite providing some context of 20th-century Chinese history, particularly in relation to Communism, this part of the narrative seemed superfluous to me; the intrigue really lies in the everyday lives of these women who have such different lifestyles and values. I am more curious about the future of these women, living in a city populated by people under 30. Do they eventually return to their rural towns? Or do they continue to live in these industrial cities, creating a new tier of the labor force, the "self-made women?" Perhaps China's industrial society still continues to evolve.

What's most remarkable about this story, as a Western reader, is our very real and legitimate connection to it. This is not a lifestyle or job contained within China's borders; rather, it's entirely a product of worldwide, and particularly U.S., demand for cheaply manufactured consumer products. These factories, and therefore these women and their choices and their lives, can attribute their very existence to our want of new iPhones. Or Nikes. Or 50" TVs. And how utterly distressing and perplexing is this?

Set primarily in the industrial town of Dongguan, Factory Girls tells a common story - that of millions of girls who leave their rural towns for a life and job in the city. As the older generation stays planted in these small, rural towns, continuing a familial tradition of agriculture, the younger generation's future has changed due to China's modern industrialization. Children, particularly the girls, leave for the factories, becoming their families' primary breadwinners. With their migration comes a new sense of freedom and opportunity in a society where education is valued but legitimacy is not (necessarily), where success depends on street smarts, and where, it seems, anything is possible if you work hard enough and smart enough for it.

Chang is a former Wall Street Journal correspondent of Chinese descent. Unfamiliar with, and a bit wary of, her own ancestry, she explores this facet of modern Chinese society from a voyeuristic perspective through select women she follows over the course of three years. She chronicles their move from job to job, always on the lookout for something better, with little loyalty or regard to particular employers; she observes friendships and relationships that seem superficial at best, entirely artificial at worst. It's a world where better jobs often come after lying on your resume, where pyramid schemes and scams run rampant to prey on hopeful ambition, and where relationships can disappear entirely with the simple loss of a cell phone.

The strength of this book lies in Chang's straightforward way of reporting the story. It's not a dastardly tale of sweatshop work. The impression I get, in fact, is that the sweatshop horrors is the stereotype of yesteryear. Though the work is certainly more monotonous and demanding of time (6-day work weeks, for example) than we are used to, the conditions, based on Chang's telling, don't seem harsh or cruel. In this sense, it's not a story of drama and hardship; it's the story of how these migrant women are constantly working for betterment. There is no passive acceptance of life; these women strive to educate themselves for better jobs and new opportunities.

|

| A factory run by TAL Group that makes US-brand apparel for such companies as J. Crew and Hugo Boss; Photo via New York Times |

Interspersed with the present-lives of Chang's migrant subjects is Chang's own family history as migrants to the U.S. after China's Cultural Revolution. Despite providing some context of 20th-century Chinese history, particularly in relation to Communism, this part of the narrative seemed superfluous to me; the intrigue really lies in the everyday lives of these women who have such different lifestyles and values. I am more curious about the future of these women, living in a city populated by people under 30. Do they eventually return to their rural towns? Or do they continue to live in these industrial cities, creating a new tier of the labor force, the "self-made women?" Perhaps China's industrial society still continues to evolve.

What's most remarkable about this story, as a Western reader, is our very real and legitimate connection to it. This is not a lifestyle or job contained within China's borders; rather, it's entirely a product of worldwide, and particularly U.S., demand for cheaply manufactured consumer products. These factories, and therefore these women and their choices and their lives, can attribute their very existence to our want of new iPhones. Or Nikes. Or 50" TVs. And how utterly distressing and perplexing is this?

Saturday, November 26, 2016

Fiction | A Logical Guide to Finding Love

November's book club selection was a lighter tome—The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion. I binge-read the entire book the Sunday before our meeting, and my ability to do that—the fact that it was such a light and quick read—made me question what kind of discussion we'd be able to pull out of this book!

Our main character is Don Tillman, a genetics professor with a slightly odd personality. His life is ruled by organization and structure; he follows the same routines daily and weekly, and he approaches life from an analytical, straightforward perspective. Unfortunately for his love life, this same perspective has never been very successful with women. When a departing friend leaves him a letter that contends he'd make a wonderful husband, Don decides it's time to find a partner. Why couldn't he find a wife using the same methodical approach as a research project?

Thus Don launches The Wife Project. By designing a thoroughly detailed 16-page questionnaire, Don figures he has created the perfect methodology to weed out the incompatible and find his perfect partner. It's a surprise to him, then, when one potential applicant named Rosie fails his compatibility test miserably...because she's the one that he can't seem to stop thinking about.

When, early in the story, his friend and fellow professor, Gene, has Don cover a lecture for him on the topic of Asperger's syndrome, it suddenly becomes very clear to the reader that this, essentially, is describing Don. [But whether Don picks up on these pointed similarities, we remain uncertain.] Though we, the reader, did not have much time with him prior to this revelation, establishing that Don is a narrator with a different way of thinking immediately changes our experience with his story. He's not your typical narrator; he tells his tale almost entirely devoid of emotion. It's a refreshing and entertaining perspective because it's such an uncommon one. In many instances, Don's logic does seem to make complete sense—and don't emotions tend to over-complicate most situations anyway??

This character that is so unused to emotional interactions, though, is in for a world of change as he builds a relationship with Rosie. Uncertain from the beginning of the nature of their relationship, Don distracts himself from such a looming question by delving into her own project of figuring out the identity of her real father. It's just the kind of study that absorbs Don's attention, using a standard method, substantive data, deductions and conclusions. In the meantime, though, Don's way of thinking begins to shift; he's loosening his hold on his routines, and his life is becoming increasingly unpredictable, almost without him realizing it.

Fortunately for the sake of our group discussion, we have an outgoing, agreeable group, so conversation was never an issue, despite this story being lighter fare. In the pop culture realm of stories of autism, we decided this was one told from a more comedic, character perspective as opposed to a dramatic, situational one. [We determined The Big Bang Theory employs this perspective as well.] Having established that we all enjoyed the story, our group was able to delve deeper into specific scenes that chronicle Don's story, discussing the author's storytelling choices and critique all the other pieces that make the story tick. It turned out to be a lively, engaging conversation, and though the story itself lacks any heavy, heady discussion points, it still has plenty to, enjoyably, consider.

Our main character is Don Tillman, a genetics professor with a slightly odd personality. His life is ruled by organization and structure; he follows the same routines daily and weekly, and he approaches life from an analytical, straightforward perspective. Unfortunately for his love life, this same perspective has never been very successful with women. When a departing friend leaves him a letter that contends he'd make a wonderful husband, Don decides it's time to find a partner. Why couldn't he find a wife using the same methodical approach as a research project?

Thus Don launches The Wife Project. By designing a thoroughly detailed 16-page questionnaire, Don figures he has created the perfect methodology to weed out the incompatible and find his perfect partner. It's a surprise to him, then, when one potential applicant named Rosie fails his compatibility test miserably...because she's the one that he can't seem to stop thinking about.

When, early in the story, his friend and fellow professor, Gene, has Don cover a lecture for him on the topic of Asperger's syndrome, it suddenly becomes very clear to the reader that this, essentially, is describing Don. [But whether Don picks up on these pointed similarities, we remain uncertain.] Though we, the reader, did not have much time with him prior to this revelation, establishing that Don is a narrator with a different way of thinking immediately changes our experience with his story. He's not your typical narrator; he tells his tale almost entirely devoid of emotion. It's a refreshing and entertaining perspective because it's such an uncommon one. In many instances, Don's logic does seem to make complete sense—and don't emotions tend to over-complicate most situations anyway??

This character that is so unused to emotional interactions, though, is in for a world of change as he builds a relationship with Rosie. Uncertain from the beginning of the nature of their relationship, Don distracts himself from such a looming question by delving into her own project of figuring out the identity of her real father. It's just the kind of study that absorbs Don's attention, using a standard method, substantive data, deductions and conclusions. In the meantime, though, Don's way of thinking begins to shift; he's loosening his hold on his routines, and his life is becoming increasingly unpredictable, almost without him realizing it.

Fortunately for the sake of our group discussion, we have an outgoing, agreeable group, so conversation was never an issue, despite this story being lighter fare. In the pop culture realm of stories of autism, we decided this was one told from a more comedic, character perspective as opposed to a dramatic, situational one. [We determined The Big Bang Theory employs this perspective as well.] Having established that we all enjoyed the story, our group was able to delve deeper into specific scenes that chronicle Don's story, discussing the author's storytelling choices and critique all the other pieces that make the story tick. It turned out to be a lively, engaging conversation, and though the story itself lacks any heavy, heady discussion points, it still has plenty to, enjoyably, consider.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Fiction | Falling for a Dead Man

As I've been reading broadly for the past two years for the (2015) Book Riot Read Harder Challenge, I've had to tackle some genres that I read rarely, if ever. That is, after all, the whole point of such a challenge—to read outside your comfort zone! One of my remaining categories has been the "romance novel," not because I have anything against romance novels but rather because I had a hard time deciding which sub-genre I wanted to read. Historical? Chick-lit? Do I look for personal plot appeal or go for a true classic of the genre?

I opted for the classic—something that is, according to pop culture & literature, truly representative of the romance genre. Having shelved books for years at the public library, I'm familiar with names, so I picked one from the depths of my memory - Jude Deveraux - and consulted Goodreads for what is considered her pinnacle work.

And that's how I got to A Knight in Shining Armor, Deveraux's 1989 bestseller that tells the story of the lovelorn Dougless Montgomery.

Our heroine is vacationing in England on what was supposed to be a romantic getaway with her surgeon boyfriend, Robert. Forever failing at love, Dougless has convinced herself that he's a good catch, worthy of her love, though it is painfully clear to us, the reader, that Robert is entirely the wrong guy; he is manipulative, controlling, patronizing—so much so that the romantic vacation, during which Dougless was hoping for a marriage proposal, has unexpectedly turned into a family one that includes Robert's brat of a teenager daughter. Any sense of romance dies swiftly when, after a nonsensical argument, Robert jilts and abandons Dougless at a rural church where she's left wallowing in yet another romantic failure, praying for a knight in shining armor to save her from the despair.

Imagine the surprise when a handsome man suddenly, miraculously appears and introduces himself as Nicholas Stafford, Earl of Thornwyck, the very name on the statue against which Dougless shed her plentiful tears. (Naturally; this is a romance!)

It's questionable who is more confused in this scenario—Dougless, whose heartbreak and frustration turn her romantic sensibilities into practical ones, assuming there's a perfectly rational explanation for this strange man suddenly appearing and claiming to be an Earl who died in the 16th century; or Nicholas, a man who heard a desperate plea for help and now finds himself in an unfamiliar world that is centuries more modern than his own.

Dougless learns of Nicholas' tragic backstory—one involving betrayal, treason, and premature death—as she helps this 16th-century earl navigate the 20th-century world. Naturally, she figures out that this impossible man is exactly who she has been praying for, and the two are inexplicably drawn together by forces that defy logical explanation and are more powerful than either can comprehend. Deveraux isn't easy on either of her main characters, forcing each of them into the time period opposite their own to continue the story and learn more of the puzzle surrounding Nicholas' sudden appearance and his tragic future. This juxtaposition of time ultimately highlights the depth of these two characters—their strengths and weaknesses. At the novel's opening, I very much found Dougless to be a major pushover but with pluck hidden somewhere underneath. As the story evolves, though, so does her character as circumstance demands a more bold, independent woman. (Though, I mean, she could still use a lot of work on the feminist front.)

So what we've got here is not only a love story but a time-traveling one—and I love time travel stories! In terms of the steamy scenes, this is definitely a romance low on that spectrum, so though yes, it's totally a romance, it feels more like an adventure based around a love story. Super fun to breeze through.

I opted for the classic—something that is, according to pop culture & literature, truly representative of the romance genre. Having shelved books for years at the public library, I'm familiar with names, so I picked one from the depths of my memory - Jude Deveraux - and consulted Goodreads for what is considered her pinnacle work.

And that's how I got to A Knight in Shining Armor, Deveraux's 1989 bestseller that tells the story of the lovelorn Dougless Montgomery.

Our heroine is vacationing in England on what was supposed to be a romantic getaway with her surgeon boyfriend, Robert. Forever failing at love, Dougless has convinced herself that he's a good catch, worthy of her love, though it is painfully clear to us, the reader, that Robert is entirely the wrong guy; he is manipulative, controlling, patronizing—so much so that the romantic vacation, during which Dougless was hoping for a marriage proposal, has unexpectedly turned into a family one that includes Robert's brat of a teenager daughter. Any sense of romance dies swiftly when, after a nonsensical argument, Robert jilts and abandons Dougless at a rural church where she's left wallowing in yet another romantic failure, praying for a knight in shining armor to save her from the despair.

Imagine the surprise when a handsome man suddenly, miraculously appears and introduces himself as Nicholas Stafford, Earl of Thornwyck, the very name on the statue against which Dougless shed her plentiful tears. (Naturally; this is a romance!)

It's questionable who is more confused in this scenario—Dougless, whose heartbreak and frustration turn her romantic sensibilities into practical ones, assuming there's a perfectly rational explanation for this strange man suddenly appearing and claiming to be an Earl who died in the 16th century; or Nicholas, a man who heard a desperate plea for help and now finds himself in an unfamiliar world that is centuries more modern than his own.

Dougless learns of Nicholas' tragic backstory—one involving betrayal, treason, and premature death—as she helps this 16th-century earl navigate the 20th-century world. Naturally, she figures out that this impossible man is exactly who she has been praying for, and the two are inexplicably drawn together by forces that defy logical explanation and are more powerful than either can comprehend. Deveraux isn't easy on either of her main characters, forcing each of them into the time period opposite their own to continue the story and learn more of the puzzle surrounding Nicholas' sudden appearance and his tragic future. This juxtaposition of time ultimately highlights the depth of these two characters—their strengths and weaknesses. At the novel's opening, I very much found Dougless to be a major pushover but with pluck hidden somewhere underneath. As the story evolves, though, so does her character as circumstance demands a more bold, independent woman. (Though, I mean, she could still use a lot of work on the feminist front.)

So what we've got here is not only a love story but a time-traveling one—and I love time travel stories! In terms of the steamy scenes, this is definitely a romance low on that spectrum, so though yes, it's totally a romance, it feels more like an adventure based around a love story. Super fun to breeze through.

Sunday, November 6, 2016

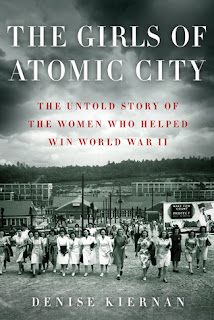

Nonfiction | A Secret Town, A Secret Mission

For my most recent book club meeting, I got to delve into some nonfiction for the first time in a while! The book was Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II by Denise Kiernan. This one has some local appeal; Oak Ridge, located just north of Knoxville, is a familiar locale to Tennesseans and, in the decades since WWII, has earned some tourist notoriety for its one-time secret status. Plus, the book group I joined skews older, so many of our readers had personal memories attached to this story, as well.

Imagine this scenario: You're living in 1943 in a nation embroiled in war, which permeates every piece of daily life. You've just finished high school or college, and with your brothers overseas fighting for your country, you have few options but to stay close to home and get a job. Then, you get this job offer with a description that could not be more vague. It seems too good to be true—the pay is outstanding and it's supposed to help win the war. Once you've secured the job, you follow the mysterious instructions you were given to take a specific train to a location you've never heard of. And once you arrive to this strange community called Oak Ridge, you settle into a new life, making new friends and doing your best every day at the job you were given. You're not really sure what's going on at Oak Ridge, but it's run by the military and therefore secretive and therefore must be helping the war cause.

This was the reality for the many women Kiernan profiles in this book. The story of Oak Ridge is a fascinating—and multi-faceted—one. This complex created by the US military, originally designed to house 17,000 workers, ultimately became home to over 62,000 individuals. These people all came to Oak Ridge for a job. From them grew friendships, relationships, a town, a community. These people became experts at their job, whatever they were, but only a fraction of 1% of Oak Ridge's residents actually knew their ultimate purpose. It was masked in secrecy, and there were constant reminders that "loose lips sink ships."

It wouldn't be until August 6, 1945, that they would figure out they had spent the last two years building the world's first deployed atomic bomb.

Perhaps now you understand why I said this story is a "multi-faceted" one. Kiernan opted to tell a particular piece of the Oak Ridge story, to view it from one perspective—that of the women whose lives were changed by this incredible reality. In this, I think Kiernan did an excellent job. She uses a handful of women to recollect the Oak Ridge experience; the reader gets to know these women as individuals—their backstories, their motivations, their fears. Through them, we understand how thousands of people united behind a common cause, despite their knowing little about it in the first place!

This is where it gets tricky for me. Naturally, my 2016 perspective is vastly different than the 1943 one of these women. And when viewed through the modern lens to which I am accustomed, this story of Oak Ridge is terrifying!

Kiernan tells this nice, patriotic, feminist story of women doing important work, but can you imagine if we heard this story in present-day terms from some country across the globe?? "Thousands Build Nuclear Weapon in Secrecy!" "Community Brain-Washed Into Building Atomic Bomb!" I understand that times were different. The war was so all-encompassing that "helping to win the war" was justifiable enough reasoning; there was little to question. Further, the mentality was different than it is today—less thirst and desire for constant information, less skepticism, fewer questions. Plus, the mere existence of these opportunities for the women of 1943, when their norms and expectations were so vastly different than today, probably fostered more excitement than suspicion.

And we haven't even touched on the debate surrounding the moral implications of dropping the atomic bomb. That's a whole other part of the story!

For what it is, I think Kiernan's book is an excellent piece of story-telling. She humanizes a piece of history while using plenty of research to create context for the reader. And she is not (and should not be) obligated to, nor responsible for, telling the whole story of Oak Ridge. But having never deeply encountered this particular piece of history myself, it opened up a can of worms

Extra: It's worth noting that our book club discussion was a pretty engaging one. Reactions and opinions seemed to run the gamut. Some women felt the same as me and had many more questions about this whole scenario; others just accepted it for what it was without much questioning. I think it's so interesting, and fosters such great discussion, because the themes go beyond this one historical scenario; it brings into question bigger ideas such as trust and fear, patriotism, society and individualism. A great one for discussion!

Imagine this scenario: You're living in 1943 in a nation embroiled in war, which permeates every piece of daily life. You've just finished high school or college, and with your brothers overseas fighting for your country, you have few options but to stay close to home and get a job. Then, you get this job offer with a description that could not be more vague. It seems too good to be true—the pay is outstanding and it's supposed to help win the war. Once you've secured the job, you follow the mysterious instructions you were given to take a specific train to a location you've never heard of. And once you arrive to this strange community called Oak Ridge, you settle into a new life, making new friends and doing your best every day at the job you were given. You're not really sure what's going on at Oak Ridge, but it's run by the military and therefore secretive and therefore must be helping the war cause.

This was the reality for the many women Kiernan profiles in this book. The story of Oak Ridge is a fascinating—and multi-faceted—one. This complex created by the US military, originally designed to house 17,000 workers, ultimately became home to over 62,000 individuals. These people all came to Oak Ridge for a job. From them grew friendships, relationships, a town, a community. These people became experts at their job, whatever they were, but only a fraction of 1% of Oak Ridge's residents actually knew their ultimate purpose. It was masked in secrecy, and there were constant reminders that "loose lips sink ships."

It wouldn't be until August 6, 1945, that they would figure out they had spent the last two years building the world's first deployed atomic bomb.

Perhaps now you understand why I said this story is a "multi-faceted" one. Kiernan opted to tell a particular piece of the Oak Ridge story, to view it from one perspective—that of the women whose lives were changed by this incredible reality. In this, I think Kiernan did an excellent job. She uses a handful of women to recollect the Oak Ridge experience; the reader gets to know these women as individuals—their backstories, their motivations, their fears. Through them, we understand how thousands of people united behind a common cause, despite their knowing little about it in the first place!

This is where it gets tricky for me. Naturally, my 2016 perspective is vastly different than the 1943 one of these women. And when viewed through the modern lens to which I am accustomed, this story of Oak Ridge is terrifying!

Kiernan tells this nice, patriotic, feminist story of women doing important work, but can you imagine if we heard this story in present-day terms from some country across the globe?? "Thousands Build Nuclear Weapon in Secrecy!" "Community Brain-Washed Into Building Atomic Bomb!" I understand that times were different. The war was so all-encompassing that "helping to win the war" was justifiable enough reasoning; there was little to question. Further, the mentality was different than it is today—less thirst and desire for constant information, less skepticism, fewer questions. Plus, the mere existence of these opportunities for the women of 1943, when their norms and expectations were so vastly different than today, probably fostered more excitement than suspicion.

And we haven't even touched on the debate surrounding the moral implications of dropping the atomic bomb. That's a whole other part of the story!

For what it is, I think Kiernan's book is an excellent piece of story-telling. She humanizes a piece of history while using plenty of research to create context for the reader. And she is not (and should not be) obligated to, nor responsible for, telling the whole story of Oak Ridge. But having never deeply encountered this particular piece of history myself, it opened up a can of worms

Extra: It's worth noting that our book club discussion was a pretty engaging one. Reactions and opinions seemed to run the gamut. Some women felt the same as me and had many more questions about this whole scenario; others just accepted it for what it was without much questioning. I think it's so interesting, and fosters such great discussion, because the themes go beyond this one historical scenario; it brings into question bigger ideas such as trust and fear, patriotism, society and individualism. A great one for discussion!

Monday, October 17, 2016

Fiction | Old Money, New South

I wrote two months ago of my plan to blog only on what inspired—to not feel pressured to reflect on every single book I read, struggling to muster up a passionate response for a reaction I did not have or feel. But for one book in particular I read last May, it's that exact passionate reaction that has left my mind blank of words. Isn't it the worst when you have so much to say but don't know how to start?

Well, it's finally gotten to the point where it's actually stressing me out to have this still lingering on my mental check-list. The very thought of composing the first words and sentences has felt too daunting to tackle. How do you convey the beauty and brilliance of one author's words when you know your own will be sub-par, unable to do it justice? Usual descriptions fall short, feeling trite and inadequate, trying too hard to emulate the power and precision of the very words you're trying to praise.

(Can you tell I'm stalling here?

Okay, okay; I'll just dive in.)

Wilton Barnhardt's Lookaway, Lookaway is the saga of one positioned, old-money, North Carolinian family. The matriarch of the Johnston clan, Jerene Jarvis, basically considers the family legacy her top priority and manages it by means only common to the old Southern elite. Her husband, Duke, is heir to a Confederate general's legacy, an All-American golden-boy turned politician whose career has floundered and has become a near-caricature Civil War re-enactor. The four kids—Annie, Bo, Joshua, and Jerilyn—are as different as they could come, almost comically so, considering the image and stature Jerene tries so hard to maintain. They're almost like a omnipresent curse on Jerene's perpetual PR campaign of the Johnston name, put in this world to make her job more complicated as they constantly threaten to shame the family name. Oh, but then there's Jerene's brother Gaston, the very definition of boozy, weird uncle—a local author renowned for his fluffy historical sagas, constantly using the stereotype of "eccentric uncle" to mask his embarrassing escapades.

So at the foundation of this novel's structure, you have this family that constantly seems to be falling apart, saved only by the influence, persuasion, and social rank of Jerene. But further up, Lookaway, Lookaway profoundly reveals the tenuous society in which the Johntson clan lives and reigns. The Antebellum period has long left North Carolina's history, but its claws dug into certain parts of society and refuse to let go. The Johnstons live in a world in which old southern ideals, money, and status still play a huge role in creating and defining the social hierarchy. But 150 years have passed since the "glory days" of the Old South, and money and power are no longer determined by a family name. The nouveau riche and opportunists threaten the Johnston position of preeminence, one they have earned by maintaining a certain way of life for decades prior. As their fortunes falter, so, it seems, does the hierarchy that defines their very identity.

What I loved about this book is how brilliantly Barnhardt captures this weird, complex, complicated entity known as "the South." I found my breath nearly taken away by certain passages that just—YES!—perfectly capture its world of contradictions. In most modern cities and towns, particularly in the South but really anywhere, it's easy for history to be pushed to the background, often nearly forgotten as the present continuously redefines; people evolve, as do the places they live.

But in some pockets of the South, the relationship with history is ever-present, so deeply ingrained in a place's identity that one cannot exist without the other. Nashville is a bustling, modern metropolis that takes great pride in its history, yes. But take a drive through Mississippi's Delta region, where two-lane highways pass through towns nearly forgotten if not already abandoned, and it's so clearly obvious that the present is a direct result of the past—that this area is still defined by its Civil War way of life, that no modern influences have shifted its story in a new direction.

I don't think Barnhardt's setting is quite so dismal and dire as this but it does successfully illustrate the social complexities existing in this lower region of the country with a dark past, complexities that are often simplified or stereotyped in fiction and culture. Combined with an intriguing cast of characters, each of whom we follow closely through that alternating-perspectives format, these observations paint a dynamic portrait of a place and people holding on tight to an identity, despite its extravagant flaws.

Well, it's finally gotten to the point where it's actually stressing me out to have this still lingering on my mental check-list. The very thought of composing the first words and sentences has felt too daunting to tackle. How do you convey the beauty and brilliance of one author's words when you know your own will be sub-par, unable to do it justice? Usual descriptions fall short, feeling trite and inadequate, trying too hard to emulate the power and precision of the very words you're trying to praise.

(Can you tell I'm stalling here?

Okay, okay; I'll just dive in.)

Wilton Barnhardt's Lookaway, Lookaway is the saga of one positioned, old-money, North Carolinian family. The matriarch of the Johnston clan, Jerene Jarvis, basically considers the family legacy her top priority and manages it by means only common to the old Southern elite. Her husband, Duke, is heir to a Confederate general's legacy, an All-American golden-boy turned politician whose career has floundered and has become a near-caricature Civil War re-enactor. The four kids—Annie, Bo, Joshua, and Jerilyn—are as different as they could come, almost comically so, considering the image and stature Jerene tries so hard to maintain. They're almost like a omnipresent curse on Jerene's perpetual PR campaign of the Johnston name, put in this world to make her job more complicated as they constantly threaten to shame the family name. Oh, but then there's Jerene's brother Gaston, the very definition of boozy, weird uncle—a local author renowned for his fluffy historical sagas, constantly using the stereotype of "eccentric uncle" to mask his embarrassing escapades.

So at the foundation of this novel's structure, you have this family that constantly seems to be falling apart, saved only by the influence, persuasion, and social rank of Jerene. But further up, Lookaway, Lookaway profoundly reveals the tenuous society in which the Johntson clan lives and reigns. The Antebellum period has long left North Carolina's history, but its claws dug into certain parts of society and refuse to let go. The Johnstons live in a world in which old southern ideals, money, and status still play a huge role in creating and defining the social hierarchy. But 150 years have passed since the "glory days" of the Old South, and money and power are no longer determined by a family name. The nouveau riche and opportunists threaten the Johnston position of preeminence, one they have earned by maintaining a certain way of life for decades prior. As their fortunes falter, so, it seems, does the hierarchy that defines their very identity.

It's as if, thought Annie, some wicked masculine committee in charge of Life had known the women would worry their pretty little heads over all this rigmarole and thereby leave the running of the big important world to the men, who would look upon all the flounces and frills, tears and hysteria, with a knowing wink, a nudge in the side, Told you that'd keep 'em occupied.

What I loved about this book is how brilliantly Barnhardt captures this weird, complex, complicated entity known as "the South." I found my breath nearly taken away by certain passages that just—YES!—perfectly capture its world of contradictions. In most modern cities and towns, particularly in the South but really anywhere, it's easy for history to be pushed to the background, often nearly forgotten as the present continuously redefines; people evolve, as do the places they live.

But in some pockets of the South, the relationship with history is ever-present, so deeply ingrained in a place's identity that one cannot exist without the other. Nashville is a bustling, modern metropolis that takes great pride in its history, yes. But take a drive through Mississippi's Delta region, where two-lane highways pass through towns nearly forgotten if not already abandoned, and it's so clearly obvious that the present is a direct result of the past—that this area is still defined by its Civil War way of life, that no modern influences have shifted its story in a new direction.

I don't think Barnhardt's setting is quite so dismal and dire as this but it does successfully illustrate the social complexities existing in this lower region of the country with a dark past, complexities that are often simplified or stereotyped in fiction and culture. Combined with an intriguing cast of characters, each of whom we follow closely through that alternating-perspectives format, these observations paint a dynamic portrait of a place and people holding on tight to an identity, despite its extravagant flaws.

Southerners. Such literate, civilized folk, such charm and cleverness and passion for living, such genuine interest in people, all people, high and low, white and black, and yet how often it had come to, came to, was still coming to vicious incomprehension, usually over race but other things too—religion, class, money. How often the lowest elements had burst out of the shadows and hollers, guns and torches blazing, galloping past the educated and tolerant as nightriders, how often the despicable had run riot over the better Christian ideals...how often cities had burned, people had been strung up in trees, atrocities had been permitted to occur and then, in the seeking of justice for those outrages, how slippery justice had proven, how delayed its triumph. Oh you expect such easily obtained violence in the Balkans or among Asian or African tribal peoples centuries-deep in blood feuds, but how was there such brutality and wickedness in this place of church and good intention, a place of immense friendliness and charity and fondness for the rituals of family and socializing, amid the nation's best cooking and best music...how could one place contain the other place?

Sunday, October 2, 2016

Fiction | Behold the Power of Books

Let me tell you how hard it is to find a good book club.

I had a four-year run with the Idlewild Book Club back in New York that was probably one of the most rewarding experiences of my post-college adult life in NYC and definitely one of the things I miss the most. Since moving back to Nashville, I've looked on and off for a new book club and tried a couple. My first experience was at our most prolific indie bookstore and while the meeting was enjoyable, the store is in the MOST annoying part of town, traffic-wise, and, being owned by an author, I'm not totally trusting on the motive behind the book choices. (The month I attended, the book just "happened" to also be released in paperback.) I'd give it another shot, but really, I just hate driving to and from that side of town.

Last month I tried one hosted by my local public library branch. It's close, which is a perk, and I've liked their book selections--less typical "book club" picks, a little more literary. My first meeting was last month for Astronaut Wives' Club, and this month we read Gabrielle Zevin's The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry. I'm still not totally loving the vibe and setting (we sit in a semi-circle around a projector screen, which makes it feel more like a lecture than discussion, and the questions are on a PowerPoint, which totally stilts the casual/natural flow of discussion, though I understand it's to help the harder of hearing), but I guess I'll keep at it for now, as long as the books are good!

Anyway, about the book...

A.J. Fikry owns and runs Alice Island's only independent bookstore, Island Books. He's a total curmudgeon and book snob. He hates bestsellers, genre fiction, and cloying memoirs; he loves literary fiction and short stories. A lot of his attitude comes from the death of his wife. She grew up on the island and they ran the bookstore together. She was the yin to his yang, but since her death, he's been in a downward spiral of negativity where he drinks, judges, and complains too much. He's mostly shut out life, but living on a small island is much like living in a small town; you see the same people every day, and everyone knows your business. It's hard to isolate yourself when people won't leave you alone.

Life is about to change for A.J. Fikry, though, and a series of seemingly unrelated events sets the change in motion. A lovely new sales rep comes to the island, persistently pushing her publisher's most sentimental titles despite the bookstore owner's rude response; A.J.'s most prized possession, a rare copy of Edgar Allen Poe poems, is stolen during one of his drunken black-outs; and then, most significant, an abandoned child appears in the bookstore with a note asking the proprietor to take care of her. Maya is a bright, loving child who quickly falls for A.J. and who quickly warms his heart as well.

So actually, reflecting on this book, it's not all that literary in nature. It's sentimental and a bit emotionally cloying. But it's also very evident that the author is writing this, essentially, as an ode to books. It avoids some of the predictable, trope-y plot twists common in narratives, and it seems pretty self-aware about that intent (meaning, it actually has successful plot twists and not just standard, predictable ones).

At the start of book club, we listened to an NPR interview with the author in which she stated her opinion that someone who says they're not a reader just hasn't found the right book yet. In her story, A.J. is such a book snob, believing certain types of books are superior to others. But the changes in his life, and the people that enter it, inspire a new open-mindedness that not only affects his opinions on books but extends beyond the page into his interactions with and opinions of the world around him. Zevin obviously believes that books have power, and I agree. Connect the right book with the right reader, and lives can be changed.

I had a four-year run with the Idlewild Book Club back in New York that was probably one of the most rewarding experiences of my post-college adult life in NYC and definitely one of the things I miss the most. Since moving back to Nashville, I've looked on and off for a new book club and tried a couple. My first experience was at our most prolific indie bookstore and while the meeting was enjoyable, the store is in the MOST annoying part of town, traffic-wise, and, being owned by an author, I'm not totally trusting on the motive behind the book choices. (The month I attended, the book just "happened" to also be released in paperback.) I'd give it another shot, but really, I just hate driving to and from that side of town.

Last month I tried one hosted by my local public library branch. It's close, which is a perk, and I've liked their book selections--less typical "book club" picks, a little more literary. My first meeting was last month for Astronaut Wives' Club, and this month we read Gabrielle Zevin's The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry. I'm still not totally loving the vibe and setting (we sit in a semi-circle around a projector screen, which makes it feel more like a lecture than discussion, and the questions are on a PowerPoint, which totally stilts the casual/natural flow of discussion, though I understand it's to help the harder of hearing), but I guess I'll keep at it for now, as long as the books are good!

Anyway, about the book...

A.J. Fikry owns and runs Alice Island's only independent bookstore, Island Books. He's a total curmudgeon and book snob. He hates bestsellers, genre fiction, and cloying memoirs; he loves literary fiction and short stories. A lot of his attitude comes from the death of his wife. She grew up on the island and they ran the bookstore together. She was the yin to his yang, but since her death, he's been in a downward spiral of negativity where he drinks, judges, and complains too much. He's mostly shut out life, but living on a small island is much like living in a small town; you see the same people every day, and everyone knows your business. It's hard to isolate yourself when people won't leave you alone.

Life is about to change for A.J. Fikry, though, and a series of seemingly unrelated events sets the change in motion. A lovely new sales rep comes to the island, persistently pushing her publisher's most sentimental titles despite the bookstore owner's rude response; A.J.'s most prized possession, a rare copy of Edgar Allen Poe poems, is stolen during one of his drunken black-outs; and then, most significant, an abandoned child appears in the bookstore with a note asking the proprietor to take care of her. Maya is a bright, loving child who quickly falls for A.J. and who quickly warms his heart as well.

So actually, reflecting on this book, it's not all that literary in nature. It's sentimental and a bit emotionally cloying. But it's also very evident that the author is writing this, essentially, as an ode to books. It avoids some of the predictable, trope-y plot twists common in narratives, and it seems pretty self-aware about that intent (meaning, it actually has successful plot twists and not just standard, predictable ones).

At the start of book club, we listened to an NPR interview with the author in which she stated her opinion that someone who says they're not a reader just hasn't found the right book yet. In her story, A.J. is such a book snob, believing certain types of books are superior to others. But the changes in his life, and the people that enter it, inspire a new open-mindedness that not only affects his opinions on books but extends beyond the page into his interactions with and opinions of the world around him. Zevin obviously believes that books have power, and I agree. Connect the right book with the right reader, and lives can be changed.

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

Fiction | How to Build an Intergalactic Hero

It's taken nearly two years (pathetic), but I'm closing in on completion of the Read Harder Challenge I began back in 2015. Naturally, the categories I have remaining are the ones I looked least forward to tackling, and among those was science fiction because mehhh, just not my thing.

I was reminded of Ender's Game this past spring when a student checked it out for his independent novel study project. I decided to use Orson Scott Card's classic as my sci-fi novel because a) it is a classic, and b) since I have it in my school library, it'd give me an advantage to know how to recommend it to my readers! Once chosen, though, I pretty much dreaded reading it based entirely on its genre. I rarely, if ever, read sci-fi, and I really didn't like the last one I did read. Also, I had no idea what the story was actually about; no doubt unfairly, I just lumped it into a genre I didn't care for, regardless of the details.

The story is about a 6-year-old boy named Ender Wiggin. He's the third child in his family, his family's third try at producing the commander who can defeat the alien army. Neither his brother nor sister proved to be "the one"—Peter has a sadistic streak, and Ender is pretty sure Peter'd kill him if he had the chance; Valentine is brilliant but an emotional liability. She is Ender's only source of comfort and protection from his older brother. Ender, though, is tough, masks his emotions, and brilliantly manages to get himself out of any scuffle in which he finds himself entangled. After one particularly brutal but triumphant encounter with a bully, Ender is recruited and sent to Battle School where he will train to become the hero the military needs in the next phase of the bugger war.

Ender thrives at Battle School and quickly proves himself to be leagues above his peers. He is able to see what's before him from a different perspective, throwing out the rules as they have been assumed. This trait does him well in the battle arena and at 10, skipping years of training, he is moved to Command School. Ender's leaders, though, increasingly isolate him and throw out seemingly impossible tasks to see how well he will handle each situation. The thing about Ender, though, is that his actions always surprise him. Strategically, he's brilliant, but the swiftness and almost ruthlessness with which he handles threats are never fully intended. To Ender, it makes him a monster, no better than Peter; to the military, he's a weapon and the best shot they have against the buggers.

I was pleasantly surprised by the successful balance of plot and character in Ender's story. As an adventure, the story is engrossing and easy to follow. Ender's world is definitely unlike our own, but the narrative never bogs down with description and reasoning; things simply are the way they are, and as a reader, you don't feel the need to question them. Ender is a character we care to follow. We meet him at such a young age, only six, which seems entirely implausible based on the complexity of the situations and conversations he encounters. But then again, it's Ender's world, and while Card does concede that Ender and his siblings are exceptional, it's mostly just a fact we accept without argument or coercion.

I never expected to like this book, but I ended up really enjoying it. It's an engrossing, accessible adventure for middle school and up kids. And beyond that, it's conceptually complex and full of content and commentary that can be read on a much deeper level—definitely a good one for literary analysis. I'm sure it is and has been analyzed to death by scholars and sci-fi fans, but it can easily be read and enjoyed at surface level, too.

I was reminded of Ender's Game this past spring when a student checked it out for his independent novel study project. I decided to use Orson Scott Card's classic as my sci-fi novel because a) it is a classic, and b) since I have it in my school library, it'd give me an advantage to know how to recommend it to my readers! Once chosen, though, I pretty much dreaded reading it based entirely on its genre. I rarely, if ever, read sci-fi, and I really didn't like the last one I did read. Also, I had no idea what the story was actually about; no doubt unfairly, I just lumped it into a genre I didn't care for, regardless of the details.

The story is about a 6-year-old boy named Ender Wiggin. He's the third child in his family, his family's third try at producing the commander who can defeat the alien army. Neither his brother nor sister proved to be "the one"—Peter has a sadistic streak, and Ender is pretty sure Peter'd kill him if he had the chance; Valentine is brilliant but an emotional liability. She is Ender's only source of comfort and protection from his older brother. Ender, though, is tough, masks his emotions, and brilliantly manages to get himself out of any scuffle in which he finds himself entangled. After one particularly brutal but triumphant encounter with a bully, Ender is recruited and sent to Battle School where he will train to become the hero the military needs in the next phase of the bugger war.

Ender thrives at Battle School and quickly proves himself to be leagues above his peers. He is able to see what's before him from a different perspective, throwing out the rules as they have been assumed. This trait does him well in the battle arena and at 10, skipping years of training, he is moved to Command School. Ender's leaders, though, increasingly isolate him and throw out seemingly impossible tasks to see how well he will handle each situation. The thing about Ender, though, is that his actions always surprise him. Strategically, he's brilliant, but the swiftness and almost ruthlessness with which he handles threats are never fully intended. To Ender, it makes him a monster, no better than Peter; to the military, he's a weapon and the best shot they have against the buggers.

I was pleasantly surprised by the successful balance of plot and character in Ender's story. As an adventure, the story is engrossing and easy to follow. Ender's world is definitely unlike our own, but the narrative never bogs down with description and reasoning; things simply are the way they are, and as a reader, you don't feel the need to question them. Ender is a character we care to follow. We meet him at such a young age, only six, which seems entirely implausible based on the complexity of the situations and conversations he encounters. But then again, it's Ender's world, and while Card does concede that Ender and his siblings are exceptional, it's mostly just a fact we accept without argument or coercion.

I never expected to like this book, but I ended up really enjoying it. It's an engrossing, accessible adventure for middle school and up kids. And beyond that, it's conceptually complex and full of content and commentary that can be read on a much deeper level—definitely a good one for literary analysis. I'm sure it is and has been analyzed to death by scholars and sci-fi fans, but it can easily be read and enjoyed at surface level, too.

Monday, September 19, 2016

Speed Dating with Middle Grade: Part 14

Title: Crown of Three

Title: Crown of ThreeAuthor: J.D. Rinehart

Genre: Fantasy

Read If You Like...: medieval magic, royal conflicts, Game of Thrones

Three-Sentence Summary: In a land ruled by a brutal king and wracked with Civil War, a prophecy brings hope of peace when illegitimate triplets of the king overthrow his reign and assume the throne. Separated at birth, the three must leave their separate lives behind and come together to save the kingdom of Toronia. The author of this must be a Game of Thrones fan because it was exceedingly complex and excessively violent for a middle grade novel.

Title: Serafina and the Black Cloak

Title: Serafina and the Black CloakAuthor: Robert Beatty

Genre: Fantasy

Read If You Like...: Historical settings, spine-tingling mysteries, Stranger Things-esque monsters

Three-Sentence Summary: Serafina and her father live secretly in the basement of the extravagant Biltmore Mansion, he as the estate's maintenance man and she as a stowaway no one knows even exists. When children begin to disappear from the estate, Serafina decides she must break her father's rule of never leaving the Biltmore's grounds and venture into the fearsome forest to investigate a mysterious man in a black cloak she believes is linked to the disappearances. The twists in this story are unexpected, and Beatty has created an unpredictable world of mystery and magic that its readers will investigate with anticipation.

Title: Drowned City: Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans

Title: Drowned City: Hurricane Katrina and New OrleansAuthor: Don Brown

Genre: Graphic Novel, Historical Fiction (yes, and ewww, 2005 is historical to middle schoolers)

Read If You Like...: Survival stories, "based on a true story" stories

Three-Sentence Summary: This graphic novel telling of Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath is simple in scope, void of individual stories and experiences. Instead, it relies on simple text and straightforward facts and numbers to convey the chaos, heroism, and racism surrounding this natural disaster. Perhaps it's intended to be a concise but thorough introduction, one that touches on all the major issues and themes, to an audience that wasn't even born in 2005, but to me it felt too simple a telling (and conclusion) of such a complex event that still has repercussions.

Title: Nightmares!

Title: Nightmares!Author: Jason Segel and Kirsten Miller

Genre: Horror

Read If You Like...: light-hearted horror (aka: the not-too-scary kind), Goosebumps, Jason Segel (obviously)

Three-Sentence Summary: Charlie's life would be okay if it was just the creepy new house and creepy new stepmom (who he's convinced is actually a witch), but when his nightmares become real, he's got a whole new problem on his hands. The line between the real world and dream world should never be crossed, and it seems up to Charlie and friends to make sure the door between the two is closed for good. The story features creepy elements but, overall, is pretty mild, serving its purpose as a light adventure read.

Saturday, September 17, 2016

Reading Roundup: History Lesson

Ingrid Betancourt's The Blue Line is a story that oozes history—that deep-set kind, full of action, consequence, and complexity kind. It'a unavoidable, you realize, when you take a look at the author's biography; Betancourt is a Colombian politician and activist, kidnapped and held hostage for six years by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). It is clear that she has drawn on her own experiences for The Blue Line, to tell the story of a passionate young woman named Julia, embroiled in the political chaos of a 1970s Argentina.

As an impressionable teenager, finding and defining her sexual and social identities, Julia falls for a revolutionary, Theo, who pulls her down a path of political idealism that becomes increasingly dangerous as the country's military dictatorship gains power. Julia and Theo's lives lose stability as trust becomes an uncertainty and safety is not guaranteed.

Amidst the growing chaos in Julia's life, she continues to live with a strange gift inherited from her grandmother—visions of the future, seen through the eyes of others. Accustomed to these apparitions, Julia has spent much of her young life fearing what she will see, beholden to the responsibility of intervening to prevent whatever horrific event she witnesses.

If this book were just all one part or the other, all politics or magical realism, it wouldn't have the appeal that it does; it would be too bogged down by its genre, producing a one-track story, narrow in its scope of storytelling. Instead, Betancourt has crafted an awesomely outlandish premise that creatively adds a different kind of excitement to the story of a dark moment in history. Though inextricably linked to its time and place, The Blue Line goes beyond historical narrative to illustrate an individual experience beyond the pages of history books.

I didn't actually realize that Lily Koppel's The Astronaut Wives Club was nonfiction until I started reading it. Using a vintage photo as cover art falls in line with the branding of a certain style of women's fiction—à la Rebecca Wells, Lorna Landvik, Laurie Graham. So needless to say, I was pleasantly surprised when I discovered this was in fact nonfiction about actual astronauts' wives during the the sixties.

Koppel has pulled together stories of the women who experienced the space race alongside their husbands in their journeys to the moon. It was a very much male-centric environment; the men were the heroes, risking their lives in a quest for glory, as their wives supported them at home. LIFE magazine was paying the families for exclusive photos and stories, chronicling the space race from the homefront, but the pressure to appear as your quintessential American family put more pressure on the women than the men. It was the 1960s after all, an era when women remained in the domestic background and outspoken feminism was frowned upon.

As a feminist women in 2016, it's quite infuriating to read about such a lifestyle and environment. Women in that era seem homogeneously lumped together as one, perpetuating this image of the perfect wife with little individuality allowed to shine through. Meanwhile, the husbands get the notoriety and recognition, not to mention the extramarital company of the "Cape Cookies" to quell their loneliness during the weeks spent at NASA's Florida base, away from their Houston homes and wives. It seems that every piece of pop culture that takes place during this era (ie: Mad Men) is filled with cheating, drinking men and submissive women, and, having not lived during the era myself, I'm beginning to believe more and more that theme is actually a realistic representation!

While Koppel tries to tell the story that existed behind the photoshoots staged for the American public, I thought that, ultimately, the story didn't delve deep enough. I don't feel as though I learned much about the women as actual people with thoughts and feelings, which should've been the purpose of this book. They still sort of seem like that homogeneous group, and whether it's because it's hard to shake the image or they actually were the subservient, voiceless wives of the era, I didn't gain any newfound respect for them.

As an impressionable teenager, finding and defining her sexual and social identities, Julia falls for a revolutionary, Theo, who pulls her down a path of political idealism that becomes increasingly dangerous as the country's military dictatorship gains power. Julia and Theo's lives lose stability as trust becomes an uncertainty and safety is not guaranteed.

Amidst the growing chaos in Julia's life, she continues to live with a strange gift inherited from her grandmother—visions of the future, seen through the eyes of others. Accustomed to these apparitions, Julia has spent much of her young life fearing what she will see, beholden to the responsibility of intervening to prevent whatever horrific event she witnesses.

If this book were just all one part or the other, all politics or magical realism, it wouldn't have the appeal that it does; it would be too bogged down by its genre, producing a one-track story, narrow in its scope of storytelling. Instead, Betancourt has crafted an awesomely outlandish premise that creatively adds a different kind of excitement to the story of a dark moment in history. Though inextricably linked to its time and place, The Blue Line goes beyond historical narrative to illustrate an individual experience beyond the pages of history books.

I didn't actually realize that Lily Koppel's The Astronaut Wives Club was nonfiction until I started reading it. Using a vintage photo as cover art falls in line with the branding of a certain style of women's fiction—à la Rebecca Wells, Lorna Landvik, Laurie Graham. So needless to say, I was pleasantly surprised when I discovered this was in fact nonfiction about actual astronauts' wives during the the sixties.

Koppel has pulled together stories of the women who experienced the space race alongside their husbands in their journeys to the moon. It was a very much male-centric environment; the men were the heroes, risking their lives in a quest for glory, as their wives supported them at home. LIFE magazine was paying the families for exclusive photos and stories, chronicling the space race from the homefront, but the pressure to appear as your quintessential American family put more pressure on the women than the men. It was the 1960s after all, an era when women remained in the domestic background and outspoken feminism was frowned upon.

As a feminist women in 2016, it's quite infuriating to read about such a lifestyle and environment. Women in that era seem homogeneously lumped together as one, perpetuating this image of the perfect wife with little individuality allowed to shine through. Meanwhile, the husbands get the notoriety and recognition, not to mention the extramarital company of the "Cape Cookies" to quell their loneliness during the weeks spent at NASA's Florida base, away from their Houston homes and wives. It seems that every piece of pop culture that takes place during this era (ie: Mad Men) is filled with cheating, drinking men and submissive women, and, having not lived during the era myself, I'm beginning to believe more and more that theme is actually a realistic representation!

While Koppel tries to tell the story that existed behind the photoshoots staged for the American public, I thought that, ultimately, the story didn't delve deep enough. I don't feel as though I learned much about the women as actual people with thoughts and feelings, which should've been the purpose of this book. They still sort of seem like that homogeneous group, and whether it's because it's hard to shake the image or they actually were the subservient, voiceless wives of the era, I didn't gain any newfound respect for them.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

Reading Notes: Gotham, Part 1

I am fairly certain I mentioned by goal of reading Gotham months ago. I even started reading it months ago. And at one point in 2016, I know had the goal of finishing the entire 1236 page book by the end of the 2015-2016 school year.

Well, now I'm three weeks into the 2016-2017 school year, and I'm still on page 75. Back during our January snow days, I breezed through Part One of the book—"Lenape Country and New Amsterdam to 1664"—and I made notes and tagged pages and then I never got around to writing about them and my continuation of reading has just been held up ever since. I've been breezing through a lot of random books lately, though, and decided that now, with my newfound motivation to read and write, is the time tomove along actually get started.

New York City is one of my favorite topics to study. For one, its centuries of transformation are amplified, more magnificently illustrated, because of its small geographic size. Tracking development as it spreads—the buildings as they rise and fall—appears grand and drastic when the area feels so contained and so easy to observe. Secondly, and related to that point, I am a witness of the city's history. I walked its streets and inhabited its buildings for a decade. I know how the traffic flows and how cultures and communities occupy neighborhoods. Knowing what came before is what inspires history nerds like me to keep reading and keep searching for clues from another time.

Because there is so much historical fact in this book that is impossible to record and remember, I think I'll focus my reading and summarizing on the state of things at any given moment in the city's history. Who was in charge? How did people live? What were the talking points, the stressors, the norms? New York is a dynamic city that changes with its population; the people are key to understanding the city's history.

Well, now I'm three weeks into the 2016-2017 school year, and I'm still on page 75. Back during our January snow days, I breezed through Part One of the book—"Lenape Country and New Amsterdam to 1664"—and I made notes and tagged pages and then I never got around to writing about them and my continuation of reading has just been held up ever since. I've been breezing through a lot of random books lately, though, and decided that now, with my newfound motivation to read and write, is the time to

New York City is one of my favorite topics to study. For one, its centuries of transformation are amplified, more magnificently illustrated, because of its small geographic size. Tracking development as it spreads—the buildings as they rise and fall—appears grand and drastic when the area feels so contained and so easy to observe. Secondly, and related to that point, I am a witness of the city's history. I walked its streets and inhabited its buildings for a decade. I know how the traffic flows and how cultures and communities occupy neighborhoods. Knowing what came before is what inspires history nerds like me to keep reading and keep searching for clues from another time.

"The city's well-merited reputation as a perpetual work-in-progress helps explain why Washington Irving's day New Yorkers were famous for being uninterested in their own past. 'New York is notoriously the largest and least loved of any of our great cities,' wrote Harper's Monthly in 1856. 'Why should it be loved as a city? It is never the same city for a dozen years together. A man born in New York forty years ago finds nothing, absolutely nothing, of the New York he knew.'"

Because there is so much historical fact in this book that is impossible to record and remember, I think I'll focus my reading and summarizing on the state of things at any given moment in the city's history. Who was in charge? How did people live? What were the talking points, the stressors, the norms? New York is a dynamic city that changes with its population; the people are key to understanding the city's history.

Friday, August 19, 2016

Fiction | Life Turned Upside-Down

We all have those movies or TV shows we love to watch because they're easy entertainment—relaxing, mindless, superficial drama that we get sucked into for however long and forget about immediately after. These "guilty pleasures" aren't things we go around sharing details about [Do I really want to brag about a 3-hour Top Model binge?], but it is culture to consume, and it is enjoyable!

I find it hard to have the same "guilty pleasure" connection to books, because I view any reading as good reading! And maybe it's something about the effort that goes into creating the product—even the most formulaic of novels has taken hours for an author to craft, with re-reads, edits, and re-writes. There's a purposeful effort behind it, more than just pointing a camera to see what happens.

So when I came to the "guilty pleasure" category of the Read Harder Challenge, I had to just pick something more entertaining than literary, something I read for fun rather than enlightenment. Ergo, I chose a Sarah Dessen novel I hadn't yet read, Just Listen.

In it, Annabel is beginning her junior year, but it's off to a rough start. Her ex-best friend Sophie will no longer speak to her—she's a social outcast now; and at home, Annabel is afraid of breaking her mother's heart by quitting her modeling career, and her older sister is struggling with anorexia, no doubt brought on by her own modeling career. We, the reader, discover that Annabel can trace all her bad juju to one night at the end of last school year. It was the night her life took a one-eighty and Sophie became her bully instead of her friend.

Annabel's only school savior is Owen, a boy she certainly would've never noticed before. He's tall, dark, and mysterious. He has a bad-boy reputation. Mostly he's just a music-obsessed outsider that doesn't care a thing about high school politics. Their burgeoning friendship gives Annabel the confidence to confront the issues that plague her and make peace with the events and people that turned her life around.

Dessen's books are wonderful—maybe one could say in that "guilty pleasure" way—because they're too serious to be fluff but too lighthearted to be heavy. They feature the everyday, realistic issues that teen girls face, and though each situation is entirely unique (as is every teenage girl), the resulting emotions are universal. Just Listen is actually probably the heaviest of Dessen's I've read, dealing with issues like sexual assault and slut shaming, though in a quieter, less upfront way than other teen novels covering the same topics. In my opinion, these are issues important for middle schoolers to read about, because they do, unfortunately, exist in their worlds. This book is a good entry into heavier talking points.

I find it hard to have the same "guilty pleasure" connection to books, because I view any reading as good reading! And maybe it's something about the effort that goes into creating the product—even the most formulaic of novels has taken hours for an author to craft, with re-reads, edits, and re-writes. There's a purposeful effort behind it, more than just pointing a camera to see what happens.

So when I came to the "guilty pleasure" category of the Read Harder Challenge, I had to just pick something more entertaining than literary, something I read for fun rather than enlightenment. Ergo, I chose a Sarah Dessen novel I hadn't yet read, Just Listen.

In it, Annabel is beginning her junior year, but it's off to a rough start. Her ex-best friend Sophie will no longer speak to her—she's a social outcast now; and at home, Annabel is afraid of breaking her mother's heart by quitting her modeling career, and her older sister is struggling with anorexia, no doubt brought on by her own modeling career. We, the reader, discover that Annabel can trace all her bad juju to one night at the end of last school year. It was the night her life took a one-eighty and Sophie became her bully instead of her friend.