Chapters 16 - 20: World War II through the Seventies. What a turbulent thirty years.

World War II--the fight against totalitarianism, racism, fascism, and militarism around the world, to "step forward as a defender of helpless countries." But Howard Zinn, being the cynic that he is, questions the real motive of American involvement. It's fact that American involvement in the war began with Pearl Harbor, when we were attacked and our link to the Pacific economy was threatened. The country rallied behind the idea of fighting for liberty, justice, and democracy. But Zinn points to how well the United States was representing liberty, justice, and democracy within its own borders--the armed forces were still segregated and blacks were still discriminated against for jobs; the status of women was little better than that of the Fascist countries we were fighting; and anti-Japanese "hysteria," as Zinn calls it, swept through the government. Zinn argues that American involvement in the war was more economic and more power-driven, despite this being a non-imperialistic war, than war propaganda of the time led the public to believe.

After reading the chapter on WWII and its immediate aftermath, I thought a great simultaneous read would be Tom Brokow's The Greatest Generation. Zinn is incredibly pessimistic and one-sided in his criticisms of the country, but his research is also very convincing. I read this book and I start to hate America. The weakness, though, in this section covering 1941-1960 is that Zinn just goes on a diatribe about how WWII had motives other than the ones the public rallied behind and he leaves out the collective conscience of the public (which he usually thoroughly analyzes!). I learned from Zinn that America quickly developed a military economy because it proved profitable (which I did not realize since I was not alive in the fifties) but what was the mindset of the American people at the time? Whether or not they were pawns in the war games of government and big businesses, the war generation is usually highly regarded as self-sufficient and united behind a cause.

Then we get to the sixties and everything just seemed to explode. Social issues had reached boiling points in society--women's rights, civil rights. Legislation that protected equal rights was not enforced. On top of the social unrest amongst the American public, the "Establishment" was tied up in international affairs. The Socialist and Communist movements across the globe--in Korea and the Soviet Union--threatened the Capitalistic society of the United States, and, as we know, the US got involved in foreign conflict to assert power and ensure continued international economic success. The Vietnam War and all its controversy seemed to be the culmination of all the conflict of the post-war era.

Now, before reading this, I am certain I could not tell you the reasons for US involvement in Vietnam (and I'm sure many would argue, "Yes, exactly!"). But even Zinn is brief in listing the reasons, and this man is not usually concise! One brief mention from a primary source states, "The countries of Southeast Asia produce rich exportable surpluses such as rice, rubber, teak, corn, tin, spices, oil, and many others.." But we all know the Vietnam conflict was presented to the public as a fight against Communism. No matter the reasons, I think this is one of the most fascinating eras of American history to read about. Massive protest and rejection of government, rule and order; critical opinion voiced loudly (very loudly); a rising suspicion of government and big business, and a strong belief in self.

And from what I gathered from the final chapter on the seventies, it sounded like an awful time of low morale and shitty government. The whole Vietnam affair made a joke of the United States, and those running the country strove to reassert American power at the expense of its people. The public was already distrustful of the government after Vietnam and political scandals like Watergate only reinforced this distrust. The American political system had been established--economy was key and the corporate class had the power.

***********************************

"...to channel anger into the traditional cooling mechanism of the ballot box, the polite petition, the officially endorsed quiet gathering." I think the point Zinn is trying to prove is that the ballot box doesn't lead to change; action leads to change, violent or not.

"...In a capitalistic society...if work is not paid for, not given a money value, it is considered valueless." The root of the issue with homemakers.

"What kind of government or society would spend millions of dollars to pick upon our bones, restore our ancestral life patterns, and protect our ancient remains from damage--while at the same time eating upon the flesh of our living People...?" Sid Mills, a Native American, October 13, 1968

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

World Party: The "Pat" situation as it appears in Trebizond

November's country in the World Reading Challenge was Turkey. I decided to search NYRB's collection, because I figured I could depend on them for some authentic world lit. So, one stroll over to Idlewild and I walked out with a copy of Rose Macauley's The Towers of Trebizond.

This is one of those books that I feel a review can't do it justice. Not because it blew me away with out-of-this-world amazingness but because it has so many angles to it. It's serious. It's religious. It's a statement. And it's actually quite funny.

Laurie is the narrator, traveling through the back country of Turkey—from Istanbul to Trebizond—with quite an eclectic English group. Aunt Dot, the middle-aged Anglican free spirit with a camel, out to reform middle Eastern views of women; Father Chantry-Pigg, traveling entirely to convert Muslims to Anglicanism; and occasionally Halide, an independent Turkish woman reformed from Islam yet preparing to marry a Muslim man. Throughout their journey, they come across many policemen who think they are spies and Billy Graham on tour with Southern evangelists. Quite the adventure.

It took a bit to fully get in engrossed its pace and language, because the writing has the quality of someone verbally telling a story. Lots of sentences full of commas that just seem to keep going, like the narrator suddenly remembered something else to say. It allows for a great subtle sense of humor, present in what-would-be the narrator's "under his/her breath" comments.

If you picked up on my ambiguity around the name "Laurie," that was intentional. Because to be honest, I STILL don't know the gender of the narrator. I read the entire book assuming it was a man. Laurie could certainly be a manly English name (c'mon, Hugh Laurie!) and the life Laurie leads is definitely not something I would expect of a 1950s English woman—traveling alone, socializing with men, drinking, training monkeys (yes, training monkeys). Yet, Laurie has a lover—a man—which came as a surprise to me at the end, particularly because that would mean this was 1950s English gay literature and it would seem far ahead of its time. But then I am reading other Goodreads comments on this book and people are using that same surprising ending to determine Laurie is, in fact, a woman. So I have no idea, and I'd rather leave it at that right now than research it. I gotta give props to the author for creating so ambiguous of a character! But like I said, this book has a lot to offer and could stand for a good second read down the road.

This is one of those books that I feel a review can't do it justice. Not because it blew me away with out-of-this-world amazingness but because it has so many angles to it. It's serious. It's religious. It's a statement. And it's actually quite funny.

Laurie is the narrator, traveling through the back country of Turkey—from Istanbul to Trebizond—with quite an eclectic English group. Aunt Dot, the middle-aged Anglican free spirit with a camel, out to reform middle Eastern views of women; Father Chantry-Pigg, traveling entirely to convert Muslims to Anglicanism; and occasionally Halide, an independent Turkish woman reformed from Islam yet preparing to marry a Muslim man. Throughout their journey, they come across many policemen who think they are spies and Billy Graham on tour with Southern evangelists. Quite the adventure.

It took a bit to fully get in engrossed its pace and language, because the writing has the quality of someone verbally telling a story. Lots of sentences full of commas that just seem to keep going, like the narrator suddenly remembered something else to say. It allows for a great subtle sense of humor, present in what-would-be the narrator's "under his/her breath" comments.

If you picked up on my ambiguity around the name "Laurie," that was intentional. Because to be honest, I STILL don't know the gender of the narrator. I read the entire book assuming it was a man. Laurie could certainly be a manly English name (c'mon, Hugh Laurie!) and the life Laurie leads is definitely not something I would expect of a 1950s English woman—traveling alone, socializing with men, drinking, training monkeys (yes, training monkeys). Yet, Laurie has a lover—a man—which came as a surprise to me at the end, particularly because that would mean this was 1950s English gay literature and it would seem far ahead of its time. But then I am reading other Goodreads comments on this book and people are using that same surprising ending to determine Laurie is, in fact, a woman. So I have no idea, and I'd rather leave it at that right now than research it. I gotta give props to the author for creating so ambiguous of a character! But like I said, this book has a lot to offer and could stand for a good second read down the road.

Sunday, December 5, 2010

Study break!

Ah people, I am sorry. I know it has been boring on here lately as I have been in the middle of my Howard Zinn reading project that is currently dragging me down as it's hit a slow, boring point. I promise I will write about a book that does not involve American history this week—Rose Macauley's The Towers of Trebizond, my November pick for Turkey in the World Reading Challenge. And I'm currently in the middle of Pinnochio, Idlewild's December book club pick, and it's a bit different than the Disney movie...

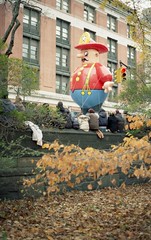

So for now, I know this is a bit late, but how was everyone's Thanksgiving? My parents visited me and we hit up the Macy's parade...good times! I've been primarily using my old 35mm camera for a few months now, and it's so fun to retrain myself to use film. I feel the style of taking pictures is so different; you have to be a little more selective with your shots, because they're limited! Photography has turned so instant with digital—and I've gotten so used to that—that the anticipation of developing your film and reliving moments you'd forgotten about is so satisfying!

So for now, I know this is a bit late, but how was everyone's Thanksgiving? My parents visited me and we hit up the Macy's parade...good times! I've been primarily using my old 35mm camera for a few months now, and it's so fun to retrain myself to use film. I feel the style of taking pictures is so different; you have to be a little more selective with your shots, because they're limited! Photography has turned so instant with digital—and I've gotten so used to that—that the anticipation of developing your film and reliving moments you'd forgotten about is so satisfying!

Friday, December 3, 2010

Reading Notes: A People's History, Part III

I'm not going to bore you to death with a long dissection of chapters 11–15. Why? Because I was bored to death with these chapters.

The previous 10 chapters had me constantly going, "Oh yes...hm...yes, good point...oh I didn't think of it from that perspective...yes." (And I'm saying that as if I had a pipe in one hand and a monocle in the other.) But this section, covering from post-Civil War to the Depression had one point. ONE. And Zinn repeated his "thesis sentence" about a billion times throughout 150 pages just by rearranging some words and changing the dates.

The rich keep getting richer at the expense of the poor, and the government uses war to distract lower-classes from organizing and rebelling.

By this point I've come to the conclusion that this is the theme of this book, because it's been the focus of all 400 pages of it I've read so far. In the seventy years covered in this section, it went like this:

The previous 10 chapters had me constantly going, "Oh yes...hm...yes, good point...oh I didn't think of it from that perspective...yes." (And I'm saying that as if I had a pipe in one hand and a monocle in the other.) But this section, covering from post-Civil War to the Depression had one point. ONE. And Zinn repeated his "thesis sentence" about a billion times throughout 150 pages just by rearranging some words and changing the dates.

The rich keep getting richer at the expense of the poor, and the government uses war to distract lower-classes from organizing and rebelling.

By this point I've come to the conclusion that this is the theme of this book, because it's been the focus of all 400 pages of it I've read so far. In the seventy years covered in this section, it went like this:

- Labor class gets exploited and people get angry.

- People start to rebel and go on strike.

- The government responds violently OR gets the country entangled in some war or foreign affair to distract people from the issues at home.

- War ends, people remember they're still angry with their own country. Cycle begins again.

At one point while reading, I just started to mark all the times Zinn rewrites his thesis in different words, so my book is filled with little margin notes that just say, "AGAIN??"

My biggest complaint about this section is that lots was going on in the country at this time, but he only writes about Reconstruction, WWI, and the Depression as they relate to labor disputes. So actually, I'm understanding this book is a very one-sided perspective. Now, I know it's easy to paint it black and white and say the working classes were victims of corporations, but there are a lot of people somewhere in the middle between the poorest of the poor and the richest of the rich. And all these perspectives are completely ignored.

So that's all I have to say on that.

**************************************

**************************************

- J.P. Morgan began business before the Civil War, during which he bought five thousand rifles from an arsenal for $3.50 each, then selling them to a general in the field for $22 each. They were defective and shot the thumbs off soldiers using them, but a federal judge upheld the deal as fulfillment of a valid legal contract. Scumbag.

- In the 1890s, alliances between farmers began the Populist movement. They created a political party that was anti-elite and against mainstream parties, got some representation in the government, and spread new ideas and a new spirit—reminds me of the whole Tea Party hubaloo. And just to note, the Populist movement crashed and burned before 1900.

- One interesting point I did not realize: all our international issues began because America was way overproductive and produced more than we could consume. So we searched for foreign markets. Or took them by force. So, see! That whole fighting an -ism (ideal) is just fluff propaganda to get the masses involved. Really, it's about money.

- When did the term "socialism" get the connotations it has today? Because according to this, EVERYONE was a socialist in the early half of the 1900s. I'm convinced the majority of people saying Obama is a socialist have no idea what the word means. I mean, the socialists DID foster the "Progressive Era," which is a GOOD thing. We have socialists to thank for housing codes, health codes, and food/drug codes. My health and living conditions thank them.

- W.E.B DuBois' "The African Roots of War" from the May 1915 issue of the Atlantic Monthly may be a good/important read.

- "A socialist critic would go further and say that the capitalist system was by its nature unsound: a system driven by the one overriding motive or corporate profit and therefore unstable, unpredictable, and blind to human needs" (p 387).

- "People organized to help themselves, since business and government were not helping them in 1931 and 1932" (p 394). We usually hear of FDR as a saint, saving the country from the Depression, but according to Zinn, he didn't have as immediate of success as we would expect. Oh hey look at that. A recession can't be fixed immediately. Things like this are why I think historical study is necessary—so people can learn from the past and gain a better grasp of how to deal with/react to present situations.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)